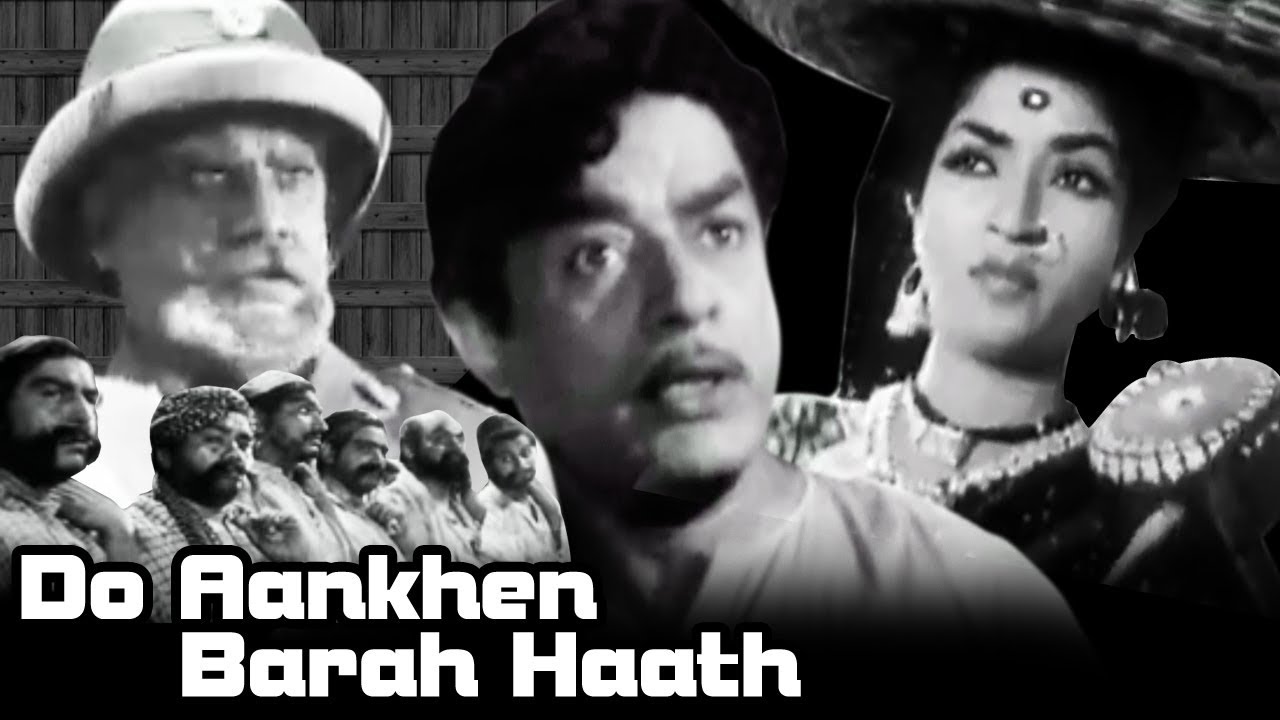

V. Shantaram’s Do Aankhen Barah Haath (1957) is a landmark in Indian cinema that beautifully blends realism with a deeply humanistic message. At its core, the film tells the story of an idealistic prison warden, played by Shantaram himself, who takes it upon himself to reform six hardened criminals. Instead of keeping them locked behind bars, he gives them a chance at redemption by assigning them to work on a barren farm. The journey is anything but easy, as they face not only external challenges but also their own inner demons. Yet, through perseverance and the warden’s unwavering belief in their transformation, the film leads to a deeply satisfying and emotional conclusion.

One of the film’s most striking aspects is its use of metaphorical representations and dialogues to communicate its underlying themes. The prison itself is symbolic of societal shackles, and the act of farming represents the criminals’ gradual moral rebirth. Scenes where the convicts struggle to till the land mirror their internal battle with their past selves. The dialogues, too, carry layered meanings, often using simple words to convey profound truths about justice, morality, and redemption. Through these artistic choices, the film ensures that its messages resonate strongly with the audience without feeling overtly preachy.

At its heart, Do Aankhen Barah Haath makes a compelling argument against a purely punitive justice system. It posits that punishment alone is insufficient; true justice is achieved when criminals are given an opportunity to rehabilitate and reintegrate into society. The warden’s compassionate approach, in contrast to a rigid and unforgiving penal system, is a testament to the film’s belief in the inherent goodness of human beings. This idea remains relevant even today, as modern discussions about criminal reform continue to emphasize rehabilitation over retribution.

The music of Do Aankhen Barah Haath is another one of its triumphs. The songs, composed by Vasant Desai and penned by Bharat Vyas, elevate the film’s emotional weight. Tracks like Aye Maalik Tere Bande Hum have stood the test of time, becoming anthems of hope and devotion. The film’s use of music is not just ornamental but integral to the storytelling, reinforcing the themes of struggle, redemption, and perseverance.

V. Shantaram’s direction is remarkable in its simplicity. He avoids excessive dramatization, allowing the natural performances of the convicts and the warden to speak for themselves. The screenplay does not rely on complex reactions or exaggerated emotions; instead, it focuses on raw, organic moments that make the characters feel real and relatable. The restrained yet powerful performances ensure that the audience deeply empathizes with the criminals’ journey toward redemption.

Ultimately, Do Aankhen Barah Haath is an extremely optimistic film that transcends eras and remains just as relevant today as it was upon its release. Its message of hope, redemption, and the triumph of human will over circumstances makes it an enduring classic of Indian cinema. V. Shantaram’s masterpiece serves as a reminder that compassion and faith in humanity can bring about transformation, making the world a better place—one reformed soul at a time.